Mechanisms of Glycine in Sleep

Thermoregulation via SCN: Glycine promotes sleep partly by lowering core body temperature through peripheral vasodilation. Research in rats showed that oral glycine triggered non-REM sleep onset faster and concurrently dropped core body temperature ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). Mechanistically, glycine acts on N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the brain’s master clock (suprachiasmatic nucleus, SCN) to dilate blood vessels in the skin, dissipating heat ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). Notably, if the SCN is destroyed, glycine’s cooling and sleep-inducing effects disappear, confirming the SCN’s critical role ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). In humans, too, glycine before bed has been observed to reduce core body temperature, similar to how nighttime melatonin works ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). This cooling effect facilitates the normal circadian drop in body temperature needed for sleep initiation.

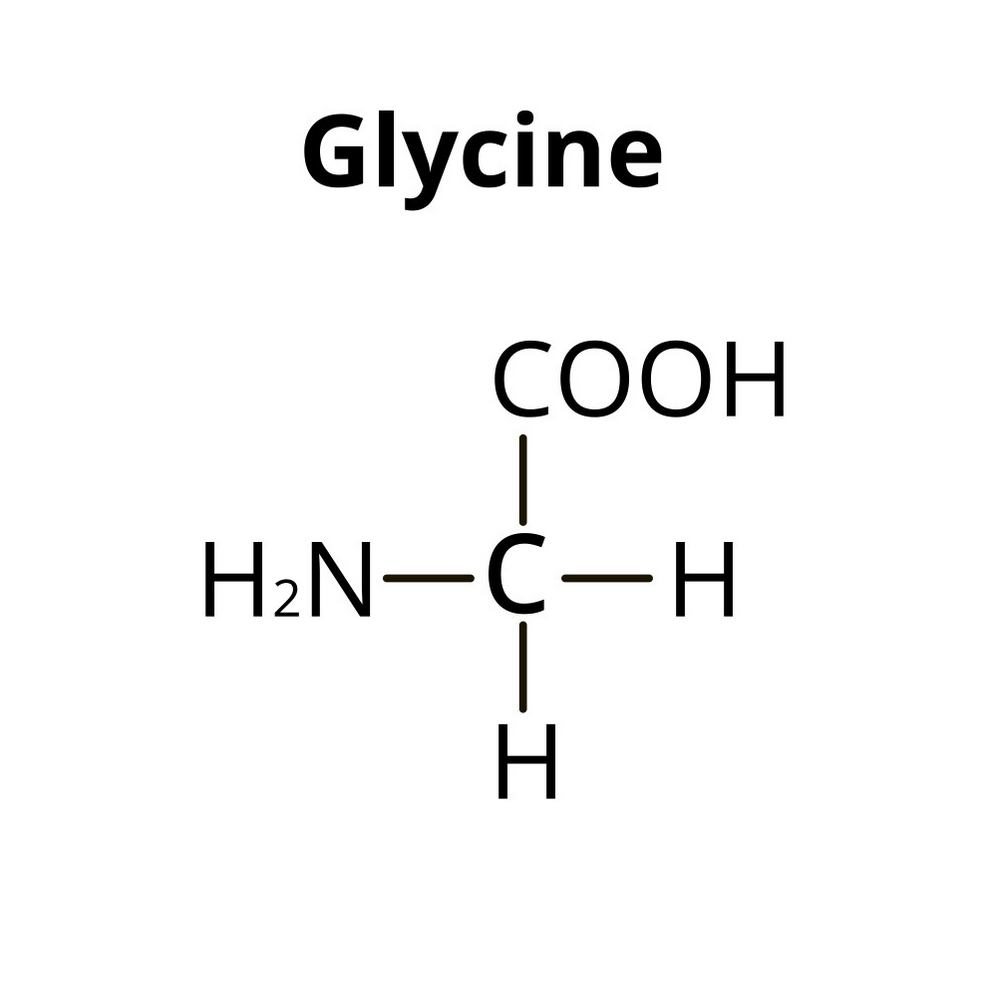

Neurotransmission: Glycine is a dual-mode neurotransmitter. In the spinal cord and brainstem it is an inhibitory transmitter that contributes to muscle atonia during REM sleep (paralysis of muscles so you don’t act out dreams) ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). Paradoxically, glycine also serves as a required co-agonist at NMDA-type glutamate receptors, meaning it can enhance excitatory signaling at those receptors ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). The sleep-promoting effect at bedtime appears to rely on the NMDA pathway in the SCN rather than the classic inhibitory glycine receptors – blocking glycine receptors with strychnine does not prevent glycine-induced vasodilation, whereas blocking NMDA receptors does ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ) ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). In essence, glycine at night likely works by stimulating a specific subset of SCN neurons (via the NMDA/glycine site) that initiate cooling and sleepiness, rather than by broadly depressing the nervous system.

Circadian modulation: While glycine acts on the circadian center (SCN), it does not shift the body’s internal clock in the way that, say, melatonin does. A human trial found no changes in plasma melatonin levels or core “clock” gene expression (Bmal1, Per2) after glycine dosing ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ). However, glycine did alter levels of SCN neuropeptides (increasing vasopressin and VIP during the day), indicating it can modulate SCN neuron activity without resetting the clock’s phase ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ). Indeed, the SCN-mediated vasodilation is a circadian output (body temperature rhythm) that glycine taps into. Authors conclude that exogenous glycine “promotes sleep by modulating thermoregulation and circadian rhythms through activation of NMDA receptors in the SCN” ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). In practical terms, glycine aligns with the circadian program (enhancing nighttime cooling) rather than forcing a phase change.

Other pathways: Glycine’s interplay with wake-promoting systems has produced mixed findings. One study in mice reported that injected glycine quieted orexin neurons (orexin/hypocretin system keeps us awake) and induced NREM sleep – albeit with fragmented sleep bouts ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). Conversely, another experiment found that when mixed with other amino acids, glycine could stimulate orexin cells more than any other amino acid ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). These contradictory results highlight that glycine’s effect on arousal circuits can depend on context (isolated glycine vs. part of a protein load) and remain an area of debate ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). Importantly, unlike sedative drugs, glycine does not fundamentally alter normal sleep architecture. In trials, glycine helped people fall into deep sleep sooner but did not distort the proportion of REM or slow-wave sleep ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ) – a sign that it improves sleep quality without disrupting the natural sleep stages.

Evidence from Human Studies

Positive Findings

Small clinical studies (mostly randomized crossover trials) consistently report that glycine supplementation before bed benefits sleep, especially in people with insomnia or sleep complaints. In a typical trial, participants with chronic sleep difficulties took 3 grams of glycine or placebo before bedtime. Glycine significantly improved subjective sleep quality – volunteers reported better “fatigue recovery,” increased clarity upon waking, and overall better sleep satisfaction (Subjective effects of glycine ingestion before bedtime on sleep quality) (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?). Objectively, polysomnography (sleep measurements) showed glycine shortened sleep onset latency (people fell asleep faster) and even slightly shortened the time to reach slow-wave deep sleep ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). Notably, one study found glycine takers spent less time awake after initially falling asleep – wake after sleep onset (WASO) was reduced by about 28% compared to placebo (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?). Sleep efficiency (the percentage of time in bed actually asleep) also improved; one trial observed a ~13% increase in sleep efficiency with glycine supplementation (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?). Importantly, these benefits occurred without any major change in the distribution of sleep stages – glycine did not suppress REM or lighten sleep, which means the sleep was not only longer but remained natural ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ).

Beyond night-time effects, next-day functioning also improved. Several studies noted that after a glycine-assisted sleep, participants felt less fatigue and daytime sleepiness the following day ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ) (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?). For example, one trial in people who slept 25% less than usual for a few nights (to simulate insomnia or restricted sleep) found that 3 g glycine at bedtime led to significantly reduced daytime fatigue and sleepiness, as measured by questionnaires and visual analog scales ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ) ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ). Reaction-time and memory tests have even hinted at better cognitive performance the morning after glycine (e.g. improved psychomotor vigilance and memory recall) ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ) (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?). In sum, these human trials – though small – consistently show glycine can subjectively and objectively enhance sleep quality and blunt the functional impairments of poor sleep. The people studied typically had insomnia symptoms or sleep dissatisfaction, so the results are most applicable to that population.

Negative or Mixed Evidence

No large-scale clinical trials have been published to definitively prove glycine as a sleep aid, and some findings urge caution. The existing studies have modest sample sizes (often only a few dozen people) and some have industry sponsorship (Ajinomoto Co., a glycine manufacturer, funded several) (Glycine Supplement Review & Top Pick – ConsumerLab.com). A 2023 systematic review noted that while multiple trials reported improved sleep in healthy or insomniac adults with glycine, these studies carried a high risk of bias and design limitations (The effect of glycine administration on the characteristics of physiological systems in human adults: A systematic review | GeroScience ). Thus, the positive results, while encouraging, should be interpreted as preliminary. So far, no placebo-controlled study has shown glycine to worsen sleep; at worst, some high-dose experiments in other contexts suggest diminishing returns. For instance, giving an excessively large single dose (around 0.8 g/kg body weight, i.e. ~50+ grams) did not further improve sleep and tended to produce negative outcomes (likely due to side effects or overstimulation of certain pathways) (The effect of glycine administration on the characteristics of physiological systems in human adults: A systematic review | GeroScience ) (The effect of glycine administration on the characteristics of physiological systems in human adults: A systematic review | GeroScience ). In other words, more is not better – 3 grams appears near optimal, and mega-doses may backfire.

It’s also clear that glycine is not a magic bullet for circadian issues. As mentioned, trials failed to find any shift in the timing of melatonin release or core clock gene rhythms with bedtime glycine ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ). This suggests that if one’s main problem is a misaligned circadian clock (e.g. jet lag or delayed sleep phase syndrome), glycine alone won’t realign it. Additionally, while one rodent study implied glycine could promote a fragmented, shallow sleep in certain conditions ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ), this has not been observed in human studies – human data actually showed stabilization of sleep (fewer awakenings) ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). Overall, there is little negative evidence per se; rather, the evidence is mostly positive but limited in scope. The chief caveat is that all supportive studies have been small and short-term. No long-term trials have yet confirmed whether nightly glycine remains effective or safe over months and whether it meaningfully improves clinical insomnia outcomes in the long run. Experts call for larger, more rigorous studies to confirm glycine’s benefits and understand which subgroups of patients might benefit most (The effect of glycine administration on the characteristics of physiological systems in human adults: A systematic review | GeroScience ) (The effect of glycine administration on the characteristics of physiological systems in human adults: A systematic review | GeroScience ).

Applications in Sleep Disorders

Insomnia and Sleep Quality

Glycine is emerging as a novel nutraceutical approach for insomnia or general sleep difficulties. Unlike traditional hypnotic drugs, glycine is an amino acid with a benign profile that modestly improves sleep initiation and quality without causing sedation or dependence. For people with insomnia characterized by difficulty falling asleep or non-restorative sleep, glycine before bedtime can be considered as an adjunct or alternative. Clinical research on mild insomnia cases showed that 3 grams of glycine at bedtime subjectively improved sleep quality and next-morning alertness ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). Many insomniacs report tossing and turning or waking frequently; glycine’s effect in stabilizing sleep and reducing middle-of-night awakenings addresses these symptoms (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?). Patients also often experience anxiety or hyperarousal at night – here glycine’s calming action on the brain may help “wind down” the nervous system (it increases inhibitory signals and tempers hyperactivity). Indeed, one study noted reduced self-reported stress and anxiety levels (a ~19% drop) when glycine was taken before sleep (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?), suggesting it may ease the mental state that accompanies insomnia.

It’s important to set realistic expectations: glycine’s effect size is moderate. People with chronic severe insomnia might find it insufficient as a standalone therapy, but those with mild or occasional insomnia can gain measurable benefit with virtually no downside. Glycine could be combined with other treatments – for example, taken alongside cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) or low-dose melatonin, to cover different bases (glycine improving sleep depth, melatonin shifting timing). Unlike prescription sleep drugs, glycine hasn’t shown rebound insomnia or tolerance. In fact, rather than causing next-day grogginess, it tends to improve next-day feelings of energy ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ) (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?). This makes glycine especially appealing for individuals who need to wake up clear-headed (e.g. professionals, students) and who want to avoid the hangover effect of sedatives. Overall, for insomnia sufferers willing to try a supplement, glycine offers a safe, evidence-backed option to modestly enhance sleep quality.

Circadian Rhythm Disorders

While glycine interfaces with the circadian system, it is not a potent chronotherapy agent. Because glycine’s sleep benefits rely on the SCN (circadian clock) being responsive to it, glycine works best when taken in alignment with one’s intended nighttime. It effectively enhances the body’s night signals – lowering body temperature and encouraging the normal night-time neural activity – but does not force a shift in the internal clock timing ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ). Therefore, for primary circadian rhythm sleep disorders (like Delayed Sleep-Wake Phase Disorder or jet lag), glycine alone cannot adjust the circadian phase. It won’t, for example, move a naturally late sleeper to fall asleep 3 hours earlier – that job is better handled by melatonin or light therapy. However, glycine can be useful as a supportive measure for circadian-related issues. If someone with a misaligned schedule is trying to sleep at a biologically suboptimal time, taking glycine might improve their actual sleep achieved at that time. For instance, shift workers who must sleep during the day (when their circadian drive for alertness is high) may benefit from glycine to promote daytime sleep by inducing some of the physiology of night (cooling, relaxation). There’s no direct study on shift workers yet, but given that glycine does not depend on time-of-day per se (it passively crosses into the brain and acts), one could take it at a “subjective night.” It could similarly help with jet lag in the sense of getting better sleep during travel – e.g. taking glycine at the target bedtime at destination might help you conk out more easily even if your body clock is still on home time.

In summary, glycine is not a circadian rhythm changer but can be a circadian rhythm helper. It modulates the SCN’s output (temperature, neuropeptides) without resetting its clock genes ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ). Researchers did observe glycine changing levels of SCN peptides like arginine vasopressin, which hints it influences aspects of circadian signaling ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ). One animal study went as far as to say glycine orchestrates sleep by working through circadian mechanisms in the SCN ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). This means glycine kind of “hacks” the circadian hardware to produce a sleep-friendly environment. For patients with circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, glycine could be combined with standard treatments: e.g. use melatonin to shift the clock and glycine to improve sleep quality during adjustment. But on its own, it should be seen as a symptomatic aid – helping you sleep at the desired time – rather than a cure for circadian misalignment. No evidence so far indicates glycine can change one’s chronotype or circadian period. Thus, its application in circadian disorders is mainly in improving sleep during the adjustment or when perfect alignment isn’t possible (such as irregular schedules).

Dosage and Safety

Dose: The typical effective dose of glycine for sleep improvement is 3 grams, taken shortly before bedtime. In most human trials, 3g consumed about 30–60 minutes before lights-out was used and yielded the benefits described (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?). This dose appears to be a sweet spot – enough to significantly impact sleep physiology, but low enough to avoid side effects. Lower doses (around 1 g at bedtime) have shown some mild benefit (for example, even 1g was reported to shorten sleep latency a bit and improve subjective sleep satisfaction (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?)), but the effects are less pronounced. Conversely, higher doses don’t seem to provide much extra sleep benefit; once you hit 3 grams, additional glycine just becomes surplus. Studies in other contexts have given glycine in much larger quantities (15, 30, even 60+ grams per day in divided doses) for purposes like neuropsychiatric treatment, but for sleep, such high doses are unnecessary ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ). In fact, extremely high single doses could be counterproductive (potentially causing discomfort or interacting with brain chemistry in complex ways (The effect of glycine administration on the characteristics of physiological systems in human adults: A systematic review | GeroScience )). So the guidance is simple: ~3 grams before bed is recommended for those looking to aid sleep. This can be taken as a powder (glycine is a sweet-tasting powder that dissolves in water) or as capsules. Taking it on an empty stomach versus with food doesn’t seem to make a big difference, although most studies had people take it post-dinner, before bed.

Safety: Glycine is generally regarded as very safe. It’s a naturally occurring amino acid – an average person already consumes around 3–5 grams per day from protein in the diet ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ), and the body synthesizes even more on its own (up to ~45 g/day endogenously) ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ). Supplementing an extra 3 grams is well within normal physiological limits. Clinical trials have not reported any serious adverse effects at the 3-gram bedtime dose or even with short-term daily use. Unlike many sleep medications, glycine does not impair driving ability the next day or cause dependence. In fact, no “hangover” effect is seen; quite the opposite, subjects often feel more refreshed ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC ). High-dose glycine studies (e.g. in schizophrenia patients, taking tens of grams per day) note that glycine is still mostly tolerated. The main side effects at very high doses (> 40 g per day) can be gastrointestinal – nausea, vomiting, and soft stool – due to overwhelming the gut with a single amino acid (Glycine Supplement Review & Top Pick – ConsumerLab.com). Such doses are far above what anyone would use for sleep. There are a few theoretical cautions: glycine in huge amounts might affect certain medications (for example, it might enhance the effects of some antipsychotics or anticonvulsants) (Glycine Supplement Review & Top Pick – ConsumerLab.com), and because it can lower blood pressure slightly, people on antihypertensives should be aware of potential additive effects on BP (Glycine Supplement Review & Top Pick – ConsumerLab.com). But again, at 3 grams these interactions or effects are minimal.

In practical terms, glycine is sold as a dietary supplement (in free form, no L- or D- isomer issues since it’s achiral). Quality testing indicates most products contain what they claim (Glycine Supplement Review & Top Pick – ConsumerLab.com) (Glycine Supplement Review & Top Pick – ConsumerLab.com). It’s inexpensive and available over-the-counter. To use it for sleep, one would dissolve ~3g in a cup of water or juice and drink it 0.5–1 hour before bedtime. Because glycine tastes sweet, some people even mix it into their nighttime tea (just be cautious of taking it with protein-rich food, as competing amino acids might reduce its uptake into the brain slightly). No tolerance to glycine’s effect has been reported – you don’t need to escalate the dose over time. As always, pregnant or breastfeeding individuals should consult a doctor before use (simply due to lack of research in those groups) (Glycine Supplement Review & Top Pick – ConsumerLab.com). Overall, glycine supplementation at reasonable doses is a safe, low-risk approach to improving sleep quality. It stands out for having physiological rationale, human trial support, and virtually no downsides – making it an intriguing tool for insomnia relief and for supporting better sleep in circadian challenges.

Sources:

- Bannai et al. 2012 – Frontiers in Neurology (Sleep Research) ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ) ( The Effects of Glycine on Subjective Daytime Performance in Partially Sleep-Restricted Healthy Volunteers – PMC )

- Yamadera et al. 2007 – Sleep and Biological Rhythms (clinical trial on glycine) ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ) (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?)

- Inagawa et al. 2006 – Sleep and Biological Rhythms (glycine pilot study) ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ) (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?)

- Kawai et al. 2015 – Neuropsychopharmacology (glycine mechanism in rats via SCN) ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC ) ( The Sleep-Promoting and Hypothermic Effects of Glycine are Mediated by NMDA Receptors in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus – PMC )

- Bannai et al. 2015 – J. Pharmacol. Sci. (glycine pharmacology, short report) (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?) (What is L-Glycine? How does it affect sleep?)

- Soh et al. 2023 – GeroScience (systematic review of glycine in adults) (The effect of glycine administration on the characteristics of physiological systems in human adults: A systematic review | GeroScience ) (The effect of glycine administration on the characteristics of physiological systems in human adults: A systematic review | GeroScience )

- ConsumerLab (independent supplement review) (Glycine Supplement Review & Top Pick – ConsumerLab.com) (Glycine Supplement Review & Top Pick – ConsumerLab.com), etc.